The British government, in an attempt to

revive its own film industry after the war, had imposed a 75% import tax on

American films shown in Britain and ordered that 45 % of the films shown in

British theaters be made in England. (A similar restriction had been agreed in

France). This was a terrible blow to the Disney studio and to make matters

worse, the French and British governments had both impounded receipts earned by

American studios in those countries, insisting that the currency be spent

there. For the Disney studio, this amounted to more than $1 million. Obviously

Walt couldn't set up an animation studio in England or France, but he had

another option. He could make a live-action film in England and finance it with

the blocked funds. In effect, then, when Walt Disney finally crossed over into

live-action, it was because the British government had forced him to do so.

Producer Perce Pearce with art director Carman Dillon

and director Alex Bryce on the 'Robin Hood' set.

and director Alex Bryce on the 'Robin Hood' set.

The project Walt selected for his live-

action feature was Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island and he dispatched

Perce Pearce and Fred Leahy to England to supervise the production. But he

remained unusually involved in the post production at least compared to the

offhanded way he had been treating recent films. He had asked Pearce and Leahy

to air-mail him specific takes for editing, and after a test screening in early

January, he ordered them to cut ten to twelve minutes and provide a more

forceful musical score; he also advised them that a more detailed criticism

would follow. Two day later he ordered the editor to fly from England to Los

Angeles, apparently so that Walt could oversee the editing himself.

The finished film, Walt Disney’s first

all live-action feature, was both a critical and financial success- unbelievably

the first in a long, long time. Treasure Island (1950) grossed $4 million,

returning to the studio a profit of between $2.2 and $2.4 million. With the

euphoria of this success was the worry that the animation side of the studio

was dying. But Walt reassured those that had raised concerns, (including

Douglas Fairbanks Jnr.) “We are not forsaking the cartoon field-it is purely a

move of economy-again converting pounds into dollars to enable us to make

cartoons here.” So in a strange turn, Disney had to make live-action films now

to save his animation.

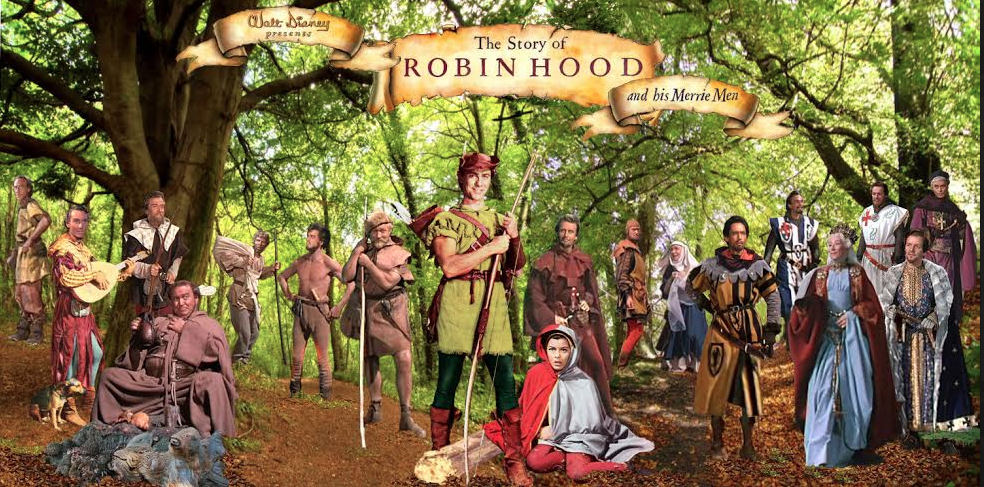

Richard Todd as Robin Hood

In July 1951, just as his cartoon

version of Alice in Wonderland was released in America, Walt Disney visited

Europe with his wife Lillian and his daughters to supervise his second

live-action movie. The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men (1952) was

financed again by the blocked monies of RKO and Disney. Before leaving, Walt

had screened films at the studio, looking at prospective actors and directors

and making what he himself called ‘merely suggestions’, while he left the final

decisions to Perce Pearce, who was producing. For his part, Pearce had laid out

every shot in the movie in thumbnail sketches, or storyboards, just as the

studio had done with the animators, and sent them on along with photostats and

the final script to Walt for his approval, which Walt freely gave, though not

without a veiled threat that Pearce had better make the film as quickly as

possible. “This is important not only to the organization but to you as the

producer,” he wrote.

Walt Disney using the Storyboard

The use of storyboards was new to ‘Robin Hood’ director

Ken Annakin, “but it appealed to my logical brain very, very much,” he said

later, and prompted ingenious scenes such as the first meeting between Prince

John and the Sheriff of Nottingham after King Richard has left, played on the

balcony of the castle against a brilliant but ominous orange sky at sundown. “I had never experienced sketch

artists, and sketching a whole picture out,” Annakin said. “That picture was

sketched out, and approved by him—but it was designed in England, and sketches

were sent back to America.” For all his influence and control, Walt was not an overbearing

studio head in Annakin’s view. “Basically, he visited the set maybe half a

dozen times, stayed probably two or three hours while we were shooting.”

Though

Walt delegated a good deal of authority on these films, he nevertheless took

his approval of the storyboards seriously. When he noticed that one sequence wasn't shot exactly as agreed, he questioned Ken Annakin as to why. Annakin

replied that he was going over budget and wanted to economize. “Have I ever

queried the budget?” Walt asked. “Have I ever asked you to cut? Let’s keep to

what we agreed.” In the end,

Annakin never wavered from his understanding that the film he was making was,

even with his own directorial expertise and perspective, and an insistence on a

more authentic telling of the Robin Hood story, a Walt Disney production.

Director Ken Annakin

Meanwhile as Robin Hood was being

filmed, Walt, Lillian and his daughters wandered through Europe, visiting the Tivoli Gardens in Denmark, and did not return to the studio until August.

While making those live action movies in England (which also included Sword and the Rose (1953) and Rob Roy the Highland Rogue (1954)), “Walt achieved something that I’m not sure he actually knew he was going to achieve”, suggests Disney authority Brian Sibley, “which was that he placed himself as being not just an American filmmaker, but also a European filmmaker—or specifically a British filmmaker. We thought of him as making films not just about us, but making them here as well. I think that that gave Britain a kind of ‘ownership’ to Walt Disney, and that only came about in the ‘50s.”

Inside the Dream: The Personal Story of Walt Disney

by Katherine & Richard Greene (2001)

Walt Disney: The Biography by Neal Gabler (2007)

So You Wanna Be A Director by Ken Annakin (2001)

w~~_12.jpg)

5 comments:

"From Animation to Live-Action"

Perce Pearce

Walt Disney

Ken Annakin

Treasure Island

The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men

Very interesting to get hold of the gross receipts for Treasure Island at around 4 million dollars. I am pretty sure that The Story of Robin Hood did better but we have never seen these figures mores the pity. I have long held the theory, which seems to be borne out by your post, that the films he made here at that time were among the most vital and important that he ever made

You forgot to give Alex Bryce a mention on the caption to the photograph on this post - and he was very important on this film. Also his daughter has been so kind and helpful also informative.I'm sure this was just an oversight though, Clement.

This latest information is very interesting.

It was a technical problem, Neil. But thanks for your help. Hopefully I have sorted it out, but Google Blogger has been giving me a lot of problems lately.

I thought it would be Clement as I know you are a fan of Alex Bryce's work on this film and others - as indeed I am

Post a Comment